The Weak Axiom of Revealed Preference (WARP): Graph Explanation

- Rahul Subuddhi

- Sep 24, 2025

- 6 min read

The Weak Axiom of Revealed Preference (WARP) is a cornerstone concept in microeconomic theory, specifically in the study of consumer choice. It provides a framework to evaluate the consistency of a consumer's preferences based on their observed choices under different budget constraints. Below, I’ll elaborate on WARP, its graphical representation, implications, and the underlying logic, while incorporating the provided graph description and summary table for clarity. I’ll also address how WARP fits into rational choice theory and its practical significance, all while keeping the explanation accessible yet detailed.

What is WARP?

WARP is a principle that ensures a consumer’s choices remain consistent across different scenarios where the same options are affordable. Formally, it states that if a consumer chooses a bundle of goods A A A (e.g., a combination of goods x1 x_1 x1 and x2 x_2 x2) over another bundle B B B when both are affordable under a given budget constraint, then the consumer should not choose B B B over A A A in any future scenario where both remain affordable. This reflects the idea that preferences, as revealed through choices, should be stable unless the economic environment (prices or income) changes in a way that affects affordability.

WARP is part of revealed preference theory, developed by economist Paul Samuelson, which seeks to infer preferences from observed behavior rather than assuming hypothetical utility functions. It’s "weak" because it imposes a minimal consistency requirement compared to stronger axioms like the Strong Axiom of Revealed Preference (SARP), which also accounts for transitive preferences across multiple choices.

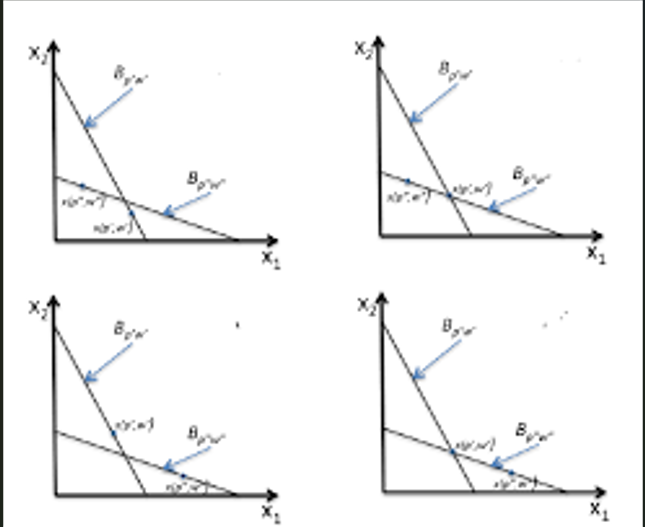

Graphical Representation of WARP

The graph described in your query illustrates WARP in a two-dimensional space, with two goods (x1 x_1 x1 and x2 x_2 x2) on the axes. Each quadrant of the graph represents different price-income scenarios, depicted by budget lines (B1,B2,B3,… B_1, B_2, B_3, \ldots B1,B2,B3,…). Let’s break down the graphical interpretation step-by-step:

Budget Lines:

A budget line represents all possible combinations of x1 x_1 x1 and x2 x_2 x2 that a consumer can afford given their income and the prices of the goods. Mathematically, for goods x1 x_1 x1 and x2 x_2 x2 with prices p1 p_1 p1 and p2 p_2 p2, and income I I I, the budget line is defined by: p1x1+p2x2=Ip_1 x_1 + p_2 x_2 = Ip1x1+p2x2=I

The slope of the budget line is −p1p2 -\frac{p_1}{p_2} −p2p1, reflecting the trade-off between the two goods. Changes in prices or income shift or rotate the budget line, creating new affordable sets.

Consumer Choice:

For each budget line (e.g., B1 B_1 B1), the consumer chooses a specific bundle, say x∗=(x1∗,x2∗) x^* = (x_1^*, x_2^*) x∗=(x1∗,x2∗), from all affordable bundles (the budget set, which includes all points on or below the budget line).

This choice reveals that x∗ x^* x∗ is preferred over all other affordable bundles under B1 B_1 B1. The arrows in the graph likely indicate this selection process, pointing to the chosen bundle on the budget line.

Testing WARP:

WARP requires that if x∗ x^* x∗ is chosen under budget line B1 B_1 B1, and in a later scenario (e.g., budget line B2 B_2 B2) x∗ x^* x∗ remains affordable (i.e., lies on or below B2 B_2 B2), the consumer must still choose x∗ x^* x∗ or a bundle that does not contradict the earlier preference.

A violation occurs if, under B2 B_2 B2, the consumer chooses a different bundle y∗ y^* y∗ even though x∗ x^* x∗ is still affordable. This would imply a preference reversal, contradicting the assumption of consistent preferences.

Quadrants in the Graph:

Top Left Quadrant: Shows the initial choice under budget line B1o B_1^o B1o, where the consumer selects x∗(B1o) x^*(B_1^o) x∗(B1o). This establishes the revealed preference.

Top Right/Bottom Quadrants: Illustrate subsequent scenarios with new budget lines (B2o,B3o,… B_2^o, B_3^o, \ldots B2o,B3o,…). If x∗ x^* x∗ is affordable under these new budget lines but the consumer picks a different bundle y∗ y^* y∗, WARP is violated.

The arrows in these quadrants likely show the consumer’s choices under each budget line, visually tracking whether the choices remain consistent with WARP.

Example of WARP in Action

Let’s consider a concrete example to illustrate WARP and its graphical representation:

Initial Scenario (Budget Line B1 B_1 B1):

Suppose a consumer has an income of $100, and the prices of goods x1 x_1 x1 and x2 x_2 x2 are p1=5 p_1 = 5 p1=5 and p2=10 p_2 = 10 p2=10. The budget line is: 5x1+10x2=1005x_1 + 10x_2 = 1005x1+10x2=100

The consumer chooses bundle x∗=(10,5) x^* = (10, 5) x∗=(10,5), meaning 10 units of x1 x_1 x1 and 5 units of x2 x_2 x2. This choice costs 5⋅10+10⋅5=50+50=100 5 \cdot 10 + 10 \cdot 5 = 50 + 50 = 100 5⋅10+10⋅5=50+50=100, which is affordable. All other bundles on or below B1 B_1 B1 (e.g., (8,6) (8, 6) (8,6), costing 5⋅8+10⋅6=100 5 \cdot 8 + 10 \cdot 6 = 100 5⋅8+10⋅6=100) are affordable but not chosen, so x∗ x^* x∗ is revealed preferred.

New Scenario (Budget Line B2 B_2 B2):

Now, suppose prices change to p1=4 p_1 = 4 p1=4, p2=8 p_2 = 8 p2=8, and income remains $100. The new budget line is: 4x1+8x2=1004x_1 + 8x_2 = 1004x1+8x2=100

Check if x∗=(10,5) x^* = (10, 5) x∗=(10,5) is still affordable: 4⋅10+8⋅5=40+40=80 4 \cdot 10 + 8 \cdot 5 = 40 + 40 = 80 4⋅10+8⋅5=40+40=80, which is less than $100, so x∗ x^* x∗ is affordable.

If the consumer now chooses y∗=(15,5) y^* = (15, 5) y∗=(15,5), costing 4⋅15+8⋅5=60+40=100 4 \cdot 15 + 8 \cdot 5 = 60 + 40 = 100 4⋅15+8⋅5=60+40=100, this violates WARP because x∗ x^* x∗ was affordable but not chosen, suggesting an inconsistent preference.

Graphical View:

On the graph, B1 B_1 B1 and B2 B_2 B2 are plotted with x1 x_1 x1 and x2 x_2 x2 on the axes. The bundle x∗=(10,5) x^* = (10, 5) x∗=(10,5) lies on B1 B_1 B1. Under B2 B_2 B2, x∗ x^* x∗ lies below the budget line (since it costs less than $100). If the consumer picks y∗=(15,5) y^* = (15, 5) y∗=(15,5) on B2 B_2 B2, the arrow pointing to y∗ y^* y∗ instead of x∗ x^* x∗ signals a WARP violation.

WARP and Rational Choice Theory

WARP is a critical component of rational choice theory, which assumes consumers make decisions to maximize their utility (satisfaction) subject to budget constraints. WARP ensures that these choices are consistent, meaning the consumer’s preferences do not arbitrarily flip when the same options are available. Here’s why this matters:

Empirical Testability:

WARP allows economists to test whether observed consumer behavior aligns with rational choice theory without needing to know the consumer’s utility function. By observing choices across different budget constraints, we can infer whether preferences are stable.

Predictive Power:

Consistent preferences (satisfying WARP) enable economists to predict future choices based on past behavior. If WARP is violated, it suggests that preferences may be context-dependent or influenced by factors outside the standard model (e.g., psychological biases).

Limitations:

WARP assumes preferences are stable over time and unaffected by factors like advertising, social influences, or changes in tastes. In reality, violations of WARP might occur due to these external factors, challenging the assumption of strict rationality.

Summary Table: WARP Rules (Expanded)

The provided summary table succinctly captures WARP’s implications. Let’s expand it with additional context:

Situation | Choice Consistent with WARP? | Explanation |

Both A & B affordable, A chosen | Yes | A is revealed preferred over B, establishing a consistent preference. |

Again, A & B affordable, B chosen | No | Choosing B when A is still affordable reverses the earlier preference, violating WARP. |

Choice switches only when A not affordable | Yes | WARP allows different choices if the original bundle is no longer affordable, as the budget set has changed. |

A chosen, B not affordable | Yes | WARP only applies when both bundles are affordable; if B is not affordable, no preference is revealed about B. |

Why Does WARP Matter?

WARP is foundational for several reasons:

Economic Modeling: It underpins demand theory, ensuring that demand functions derived from consumer choices are consistent and predictable.

Policy Analysis: Policymakers rely on consistent consumer behavior to predict responses to price changes, taxes, or subsidies.

Behavioral Economics: Violations of WARP in real-world data can highlight deviations from rationality, prompting research into behavioral factors like framing effects or choice overload.

Potential Violations and Real-World Context

While WARP assumes rational and consistent behavior, real-world choices may violate it due to:

Changing Preferences: A consumer’s tastes may evolve (e.g., preferring tea over coffee after a health scare).

Contextual Factors: Marketing, peer influence, or emotional states can lead to preference reversals.

Incomplete Information: Consumers may not fully understand their options, leading to inconsistent choices.

Graphically, these violations would appear as arrows pointing to different bundles under budget lines where the original bundle remains affordable, signaling a break in consistency.

Conclusion

The Weak Axiom of Revealed Preference is a fundamental principle that ensures consumer choices reflect stable preferences under consistent affordability conditions. The graph you described visually captures this by showing budget lines and choice arrows across different scenarios. By requiring that a consumer sticks with a previously chosen bundle when it remains affordable, WARP enforces rationality and consistency, making it a powerful tool for economic analysis. However, its assumptions of stable preferences highlight its limitations in capturing real-world complexities, where psychological and external factors often influence choices.

_edited.jpg)

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

etc mining etc mining

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

etc mining etc mining

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

etc mining etc mining

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

etc mining etc mining

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

monero miners monero miners

etc mining etc mining